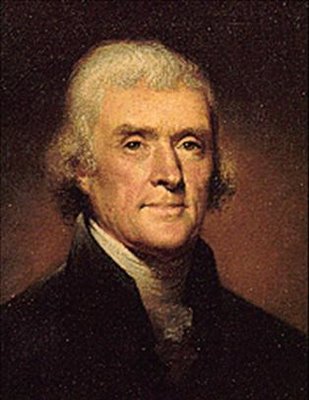

THOMAS JEFFERSON:

A DEFENSE OF HIS CHARACTER

|

Thomas Jefferson, April 15, 1806.

"He who permits himself to tell a lie once, finds it much easier to do it a second and third time, till at length it becomes habitual; he tells lies without attending to it, and truth without the world's believing him. This falsehood of the tongue leads to that of the heart, and in time depraves all its good dispositions."

(Letter to Peter Carr, September 19, 1785)

Thomas Jefferson

"The order of nature [is] that individual happiness shall be inseparable from the practice of virtue."

(Letter to M. Correa de Serra, 1814).

"Without virtue, happiness cannot be."

(Letter to Amos J. Cook, 1816).

"Happiness is the aim of life. Virtue is the foundation of happiness."

(Letter to William Short, October 31, 1819).

Thomas Jefferson

"When it became clear that he was not going to be offered any government post, the embittered Callendar sought revenge by going to work for a Federalist newspaper in Richmond. In March 1802, he began publishing various charges against Republican leaders in Congress and certain members of the Cabinet. By autumn he was training his guns on the President [Thomas Jefferson]."

". . . True to his style, he fabricated a series of scandalous stories about Jefferson's personal life, the ugliest of which charged him with having fathered several children by a mulatto slave at Monticello, a young woman named Sally Hemmings. . . . He included many lurid details of this supposed illicit relationship . . . even inventing the names of the children whom [she] had never born. [see, Malone, Jefferson the President: First Term, 1801-1805, pp. 206-23]."

"Other Federalist editors took up these accusations with glee, and Callendar's stories spread like wildfire from one end of the country to the other -- sometimes expanded and embellished by subsequent writers. [almost every scandalous story about Jefferson, both then and now, can be traced to Callendar (who drowned himself in the James River in 1803)]."

"Like other men, Jefferson was sensitive to these false accusations. . . Publicly, however, he made no response to these unsrcupulous attacks. 'I should have fancied myself half guilty,' he said, 'had I condescended to put pen to paper in refutation of their falsehoods, or drawn them respect by any notice from myself.' [Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Dr. George Logan, June 20, 1816]. Nor did he use the channels of civil authority to silence his accusers. True to the declarations he had made in his inaugural address and elsewhere, he defended his countrymen's right to a free press."

". . . [Regarding this issue], one of the recently discovered documents . . . [is] a letter written by nineteenth century biographer Henry Randall (who published a three volume biography, Life of Jefferson (1858)), recounting a conversation at Monticello between himself and Jefferson's oldest grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph. In this conversation Randolph confirmed . . . that 'there was not the shadow of suspicion that Mr. Jefferson in this or any other instance had commerce with female slaves.' [See also, "The Jefferson Scandals" (1960), Fame and the Founding Fathers: Essays by Douglass Adair, ed. Trevor Colbourn (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1974), pp 169.]"

". . . 'Colonel Randolph said that he had spent a good share of his life closely about Mr. Jefferson, at home [Jefferson never locked his bedroom door by day and left it open at night, Colonel Randolph sleeping within the sound of his breathing at night] and on journeys, in all sorts of circumstances, and he fully believed him chaste and pure -- as "immaculate a man as God ever created." [Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868).]"

Quoted from: Allison, Maxfield, Cook & Skousen,"The Real Thomas Jefferson" (2d Ed., National Center for Constitutional Studies, Washington, D.C., 1987), pp. 227-234 [commentary in brackets added].

Randall also wrote that Jefferson's daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, "directed her sons' attention to the fact that Mr. Jefferson and Sally Hemings could not have met-were far distant from each other-for fifteen months prior to the birth" of Eston Hemings -- the child who supposedly most resembled Jefferson. As noted by historian David N. Mayer (see below), almost everyone has assumed that Mrs. Randolph was referring to Jefferson's absence from Monticello at that time, but she may very well have been referring to Sally Hemings'. For the complete text of Randall's letter, see: Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton, June 1, 1868

."We are asked to believe this U.S. minister to France, a man with ready access to some of the most beautiful and accomplished women in Europe, initiated an affair with a 15 or 16-year-old slave girl, whom Abigail Adams had recently described as more in need of care than the 8-year-old she had attended. This girl was the personal servant (and likely something of a confidant) of Jefferson's two daughters—an individual, that is, whose discretion the accomplished politician and diplomat could not possibly have trusted. Although it may well be that Sally lived, during much of her time in Paris, in the cross-town convent where Patsy and Polly were being schooled, we are to assume that Thomas and Sally carried on their affair in the crowded two-bedroom townhouse where Jefferson lived—and did so without arousing suspicion of David Humphreys, who slept in one of the bedrooms, or of anyone else who was there. She became pregnant with Jefferson's child, the story continues, entered into an agreement with him, and (with Jefferson taking care that she would have a berth convenient to his daughters) sailed back to the U.S. in this condition with him, his two girls, and her brother James. The baby, if it existed, either died soon after birth, leaving no trace other than Madison Hemings's statement, or became the elusive, unrecorded 12-year-old slave named "Tom," mentioned in James Callender's infamous 1802 newspaper accusation, who, if he later took the name Tom Woodson, was not Thomas Jefferson's child.

According to this story, Jefferson would continue in a monogamous and fertile relationship with Sally for nearly 20 years, ultimately fathering five or six more children (the first of whom, however, was not born until 1795). During these twenty years, he was content, as was she, to confine the relationship to the times when he was at Monticello, although he took other slaves with him wherever he went and as many as a dozen to the White House. On these terms, he continued in the relationship until at least age 64, when Eston Hemings was conceived, five years after he had been publicly accused of a relationship with Sally and while he was contemplating his second presidential term. He carried it on, all this while, while constantly surrounded by visitors and by a large white family, none of whom—and least of all the daughters who would have known Sally best—ever had the least suspicion that he was involved with any of his slaves or ever saw the slightest indication that he was closer to Sally than to any other servant.

Indeed, the grandchildren who grew up at Monticello and managed it during Jefferson's last years did not merely say that any such relationship was wholly unsuspected—never a touch or a word or a glance—they said it was simply impossible in this particular house. "His apartment," his granddaughter told her husband, "had no private entrance not perfectly accessible and visible to all the household. No female domestic ever entered his chambers except at hours when he was known not to be there and none could have entered without being exposed to the public gaze." In fact, apart from Madison Hemings, no one who ever lived at Monticello and none of the uncounted visitors who stayed there overnight ever said that he was involved with Sally—not even Sally herself, though she lived in practical freedom in Charlottesville for ten years after his death.

It is possible, of course, that everyone except Madison Hemings was lying or covering up or engaged in psychological "denial." Jefferson's family had an interest in protecting his reputation, much as Madison Hemings had an interest in claiming descent from a famous man. I see no reason to think that any of these people were deliberately making things up. What of eye-witnesses who had no obvious interest in the matter either way? Former household slave Isaac Jefferson mentioned Sally Hemings in later years; but did not so much as hint that there was any special relationship between her and Jefferson. And in another interview, Edmund Bacon, who was overseer at Monticello when Eston was conceived and may have worked there for years before, raised the subject of the accusations against his employer.

He freed one girl some years before he died, and there was a great deal of talk about it. She was nearly as white as anybody, and very beautiful. People said he freed her because she was his own daughter. She was not his daughter; she was ______'s daughter. I know that. I have seen him come out of her mother's room many a mourning, when I went up to Monticello very early.

The girl was certainly Harriet Hemings, Sally's daughter. The father was named by Bacon but protected by the reporter, a preacher in Kentucky.

All of Sally Hemings's children who lived to adulthood did achieve their freedom, either de facto or de jure, and it is often said that they were the only nuclear family of Monticello who did. However, contrary to the terms of the "treaty" as Madison Hemings described it, Sally Hemings did not receive extraordinary privileges at Monticello. Jefferson fed, clothed, and treated Sally Hemings pretty much indistinguishably from his other household servants, recorded her life and childbirths in much the same way, and left her as part of the estate. By Madison Hemings's own account, moreover, Jefferson showed no particular affection for her children and reared them much as he did other household slaves. Can we believe that Jefferson, always concerned for contemporary and historical regard, would not only have continued an affair with Sally long after it became a public scandal—and still without arousing his family's suspicion—but would have been so brazen about it as to have a slave whose resemblance to him was absolutely startling serve his foreign guests at dinner?"

Quoted from: "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: Case Closed?" by Lance Banning, (The Claremont Institute, August 30, 2001).

EDITOR'S NOTE: "Nature" magazine's DNA article on Jefferson (which came out a few days before the November 1998 election) was flawed because it had failed to mention that there were at least eight (8) other Jeffersons who might have fathered children by Sally Hemings since the DNA for the test came from Jefferson's uncle -- not Jefferson himself (almost all of whom were known to have visited Monticello frequently). Additionally, there is always a possibility of later DNA contamination from the Jefferson line with the Hemings line.

"Nature" magazine's follow-up explanation states that the conclusion [title] of its previous article was misleading -- in that it represented only "the simplest explanation," and acknowledges that [among others] Isham Jefferson, son of Thomas Jefferson's brother Randolph, might have been the father of one or more of Sally Hemings' children, but concludes that: " From the historical knowledge we have [i.e., no proof that Isham was at Monticello during relevant times], we cannot conclude that Isham, or any other member of the Jefferson family, was as likely as Thomas Jefferson to have fathered Eston Hemings [i.e., since Jefferson lived at Monticello]."

A fact that went largely unreported was that the DNA test did rule out Thomas Jefferson as the father of Thomas Woodson, the eldest of Hemings' sons, and shed no definitive light on the rest (obviously, Sally may have had more than one paramour, as did her mother). We are left with the conjecture that his supposed relationship with Hemings continued for twenty years (unbeknownst to his family and freinds) until Jefferson was at least 65 years old . . . .

For excellent articles that address the subject of the DNA tests, see: "Thomas Jefferson-Sally Hemings, The DNA Study"

The Bible teaches "by their fruits ye shall know them."

The history and writings of Jefferson evidence a consistent

moral integrity and honesty throughout his life -- and a rising star, not a

fallen one.

With respect to slaves, Jefferson actually did more during his life against slavery

than most other men of his time -- and deserves the credit for the

principles in the Declaration of Independence that "all men are created

equal" -- which in the hands of Lincoln and Divine Providence, eventually

freed the slaves -- at a great price of human blood in the Civil War.

Jefferson's anti-slavery efforts include:

1. Introduction of a bill in 1769 the Virginia legislature to abolish the importation of slaves into that state.

2. Inclusion of an anti-slavery provision in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

3. Initiated the Congressional ban on slavery in all federal lands in 1784 (his effort to extend the act to the 13 states lost by only one vote).

4. In 1808, as President, he signed into law a bill banning the slave trade with Africa.

While Jefferson did not free all of his slaves on his death (as did Washington), a law passed in Virginia in 1806 required that the legislature pass a special bill that would attest to the exemplary behavior of each slave to be freed. If freed, the slave had to leave the state without his or her family. Jefferson was not in favor of this law. Further, Jefferson trained his slaves in skills that would be useful when they were free. He believed that to free them first would be irresponsible -- since they would be homeless and without family.

To those who will read and search for themselves and discern the honest from the dishonest, and the man of moral principle from one who is not, I believe the truth becomes more clear as to the greatness and stature of Thomas Jefferson.

and to leave motives to Him who can alone see into them."

Thomas Jefferson

J. David Gowdy

jdgowdy@wjmi.org